Schriesheim on the Badische Bergstrasse has missed a lot. Winegrowers like Pascal Treichler could wake up the region.

I have to confess: I’m not entirely unbiased on the subject. As a Bergstrasse native, the viticulture of my home region is somehow dear to my heart. Especially because it never played a major role in my childhood. My parents had a hobby vineyard in Schriesheim for a few years. Vines do indeed grow in my home town of Weinheim and its neighbouring villages. But I only learnt about a collective winegrowing identity later from stories of winegrowers from the Palatinate, the Rheingau or the Kaiserstuhl. There was never a harvest mood that spread across entire villages, professions and generations. I didn’t know any winegrowers’ children either. When I started to take an interest in wine, I almost forgot that I lived in a wine-growing region. In my mind, wine always existed somewhere else: in the Palatinate on the other side of the Rhine Graben or in the Kaiserstuhl; but not on my doorstep, even though I would cycle through some vineyard almost every day. In terms of viticulture, the Bergstrasse remained grey. Apart from Thomas Seeger on the other side of the Bergstrasse, which didn’t feel like home anymore, there wasn’t a single interesting winegrower on the Badische Bergstrasse back then. The vineyards were – and still are – in the hands of the farmers and co-operative winegrowers, who delivered their grapes to the Schriesheim cooperative. which did not produce its own wine but transported the musts to the huge Badischer Winzerkeller in Breisach.

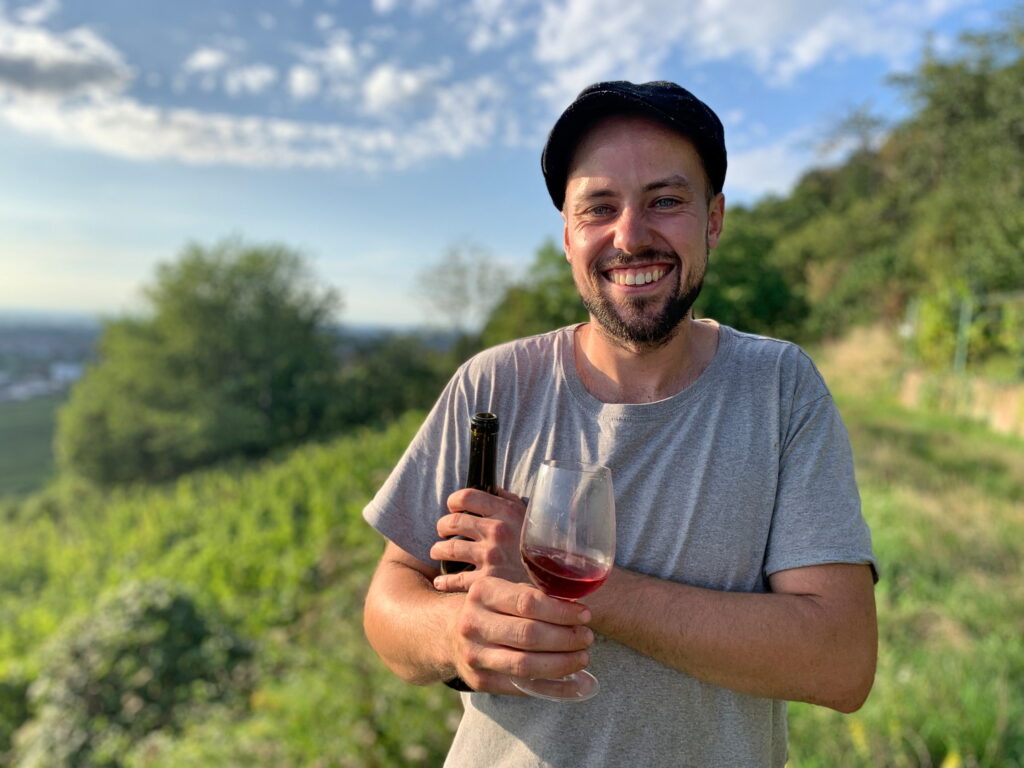

But that’s enough about me. Luckily, there are now at least two winegrowers in Schriesheim who are doing a very good job. A few years ago, Max Jäck took over the family winery and is changing Schriesheim with his subtly natural style. Since 2021, young winemaker Pascal Treichler in particular has been rocking the village. With sulphur-free wines, permaculture and fruit trees in the middle of the vineyard, his own vinegars, cider and apple wine.

Pascal Treichler: in search of funk and authenticity

He clearly describes his wine style as natural wine. He neither filters nor fines, not even with sulphur. In the cellar, I try a 2022 Pinot Noir from the barrel, which was macerated for four weeks and has a wild but juicy flavour, with blackberries, blackberry leaf tea, dark fruit and charming bitter tones. For me, the wine is characterised by a great balance, for Pascal it is a little too clean. For the 2023 vintage, he therefore decided not to punch down the first few days in order to intentionally evoke an accumulation of acetic acid bacteria on the surface that has not been sterilised by fermentation CO2. He wants the wines to be wild and funky. I haven’t tasted the new vintage yet, but I suspect I’ll be more comfortable with the relatively pure and clear 2022s. But Pascal Treichler doesn’t make wine for me, and I always welcome it when winemakers develop their own style.

The Roter Rebell is also excellent. It is an early harvested Pinot Noir in the style of a Vin de Soif, which is best drunk chilled in large sips. This allows the flavours of fresh, acidic blackberries and elderberries to unfold best. The Anarchie white wine is also very unique, made from a blend of Pinot Blanc, Pinot Gris and various muscat varieties. It has wonderful bitter tones, vermouth, rooibos tea, lemon peel and Kalamata olive brine. Without a doubt, you have to like natural wine to understand Pascal Treichler’s wines. But for me they never seem too fashionable or overly intellectual, even though he makes no compromises when it comes to the use of additives and permaculture.

Pascal has turned some of his vineyards into gobelets on single poles: “The idea behind it is to go back to the roots. That’s how it used to be done. For manual labour, the wire trellis is just annoying and gobelets cope better with drought and the vines are more durable”.

“I sometimes get a bit of a weird look when I walk through the village with the pickaxe over my shoulder,” says Pascal, who comes from Eiffel and is employed as a winemaker’s assistant by the previously mentioned Max Jäck. He cultivates his own 1.5 hectares as a side business without machines. Partly because this suits his philosophy, but also because the small parcelled vineyards right at the edge of the forest are usually not suitable for tractors anyway.

Cru de Hobby

The dominance of the Schriesheim cooperative has created a strange structure in the vineyards at the foot of the Odenwald. For the co-operative winegrowers, who are paid by Brix, the manual labour that is required here in the old plots makes no sense. But there are hardly any winegrowers in Schriesheim who vinify their own grapes. Around Pascal Treichler’s vineyards there are almost exclusively hobby vineyards that people cultivate for leisure. As I walk with Pascal through the upper part of the old Schriesheimer Kuhberg, which merges seamlessly into the Dossenheimer Ölberg, I also see many vineyards that are becoming overgrown. “I could take over five hectares immediately,” he says with certainty. Most of them are first-class sites with many old Pinot Noir vines, but nobody wants to cultivate them any more.

The crisis in cooperatives as a driver of innovation

As early as 1948, Schriesheim favoured Pinot Noir, which today accounts for almost half of the vineyards. The old vines in the Schlossberg, Schriesheim’s traditional steep top site below Strahlenburg Castle, fell victim to relentless land consolidation in 2006. This part of Schriesheim has become uninteresting for winegrowers like Pascal Treichler, who wants to produce top wines within his niche. The same thing has also happened in the Kaiserstuhl, where artificial large terraces are also of no interest to renowned winegrowers.

As much as land consolidation and the crisis of the cooperatives undermine the preservation of traditional vineyards, their positive side effect is clearly evident. In almost all regions with a social structure shaped by cooperatives, vineyards are very easy to obtain. In most cases, vineyards that are good for quality but uneconomical within the cooperative price and cost structures are particularly easy and cheap to obtain. For young winegrowers without inheritance who have the courage to develop top sites themselves instead of relying on the existing reputation of Rotem Hang, Berg Schlossberg or Pechstein, the time to found a winery is better than ever. The story of Pascal Treichler and Schriesheim can therefore be seen as representative of the many young winegrowers in crumbling winegrowing communities. The fact that their wines are often so promising could lead to a wakeup moment.